Rethink Your Grazing

Transform Your Pastures with

Rotational Grazing

Rotational grazing can be customized to fit your herd and land. While setup averages $70–$75 per acre, long-term savings on feed, fertilizer, and vet bills quickly outweigh the cost. The practice leads to healthier soils, improved pastures, reduced parasite pressure, and stronger herd performance. With pasture planning and record keeping, it becomes easier to manage pasture rotations and measure results over time.

How Rotational Grazing Works

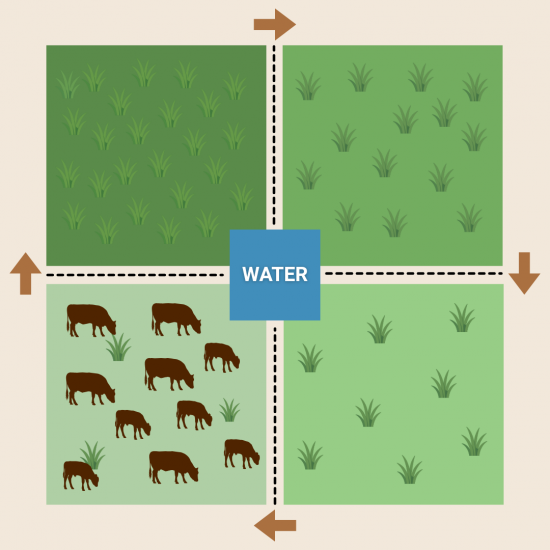

Rotational grazing is the practice of dividing pastures into smaller paddocks, or sections, and moving livestock between them on a planned schedule. While one section is being grazed, the others are left to rest and regrow. This cycle helps restore nutrients to the soil, encourages stronger forage, and makes more efficient use of pasture resources.

The biggest difference is how rotational grazing compares to continuous systems:

- Continuous grazing: Animals stay in one large area for an extended time. It has a lower upfront cost and requires less management, but often leads to overgrazed pastures and lower carrying capacity.

- Rotational grazing: Requires more planning but supports higher stocking rates, builds soil health, and naturally reduces weed pressure.

This contrast explains why so many producers are making the shift. Continuous systems may be easier in the short term, but rotational systems consistently deliver stronger long-term productivity and resilience.

The principle is simple: graze, rest, regrow. Success comes down to managing timing, recovery, and stocking rates with consistency.

Building Healthier Pastures

Healthy pastures depend on planned rest. Allowing sections to recover between grazing periods encourages deeper root systems, which improve soil fertility and organic matter. This reduces the need for purchased fertilizer and helps pastures withstand stress during drought or heavy rains. The NRCS generally recommends at least 20 days of rest for a section, though this may extend to 40 days during slower growth periods.

Rotational grazing also improves water use and erosion control. By keeping pastures covered with living plants, rain is absorbed more effectively, runoff is reduced, and soil stays in place. Healthy root systems hold moisture longer, giving forages a buffer against dry spells.

Parasite control is another natural benefit. When animals move to fresh paddocks, they leave behind manure that parasites rely on. With no new hosts available, parasite life cycles are broken, reducing veterinary costs and improving herd health.

Monitoring is an important part of the system. Tools like a pasture plate meter can measure forage height and density, guiding decisions on when to move cattle and how long to rest each section. Ranchers also watch for signs such as plant regrowth, soil moisture, and animal condition to fine-tune their rotation schedules.

Setting Up Your Grazing System

Getting started with rotational grazing requires some investment in fencing, water systems, and possibly pasture renovation. While costs vary, estimates place initial setup around $70 per acre for smaller acreages (up to 100 acres) and closer to $10 per acre for larger acreages (400 or more).

Temporary electric fencing is a popular choice for beginners because it is affordable, portable, and easy to adjust. Step-in posts and polywire can be moved to resize sections based on forage growth or herd size. Portable water troughs and pump systems also provide flexibility, allowing ranchers to supply clean water wherever it’s needed. For those planning long-term systems, permanent cross-fencing and underground water lines offer durability and efficiency, though with a higher upfront cost.

Producers often find that these investments pay off quickly. In Virginia, ranchers reported an additional $200 per animal per year after adopting rotational grazing. In Oregon, a cattle producer reduced his hay feeding by nearly two months annually. Smaller sections also save time during herd checks, cutting labor costs.

There are several ways to implement rotational grazing, depending on management goals:

- MIRG (Management Intensive Rotational Grazing): Follows a set schedule based on projected forage growth.

- AMP (Adaptive Multi-Paddock Grazing): Adjusts daily to factors like rainfall, plant recovery, or herd needs.

- Mob grazing: Uses high animal density in small paddocks for short periods, trampling residue to build soil.

- Strip grazing: Narrow strips are grazed in sequence to maximize forage use.

- Silvopasture: Incorporates trees into pastures to provide shade, reduce wind damage, and create additional income from fruit, nuts, or timber.

Each approach has strengths, but all rely on the same principle: giving pastures rest to recover and regrow.

Managing and Adapting Your Grazing Plan

Forage selection is another key piece of rotational grazing. Depending on climate and soil type, ranchers may plant cool-season grasses, warm-season grasses, or grass-legume mixtures. Cool-season grasses can extend grazing days into the colder months, while legumes improve protein levels and naturally fix nitrogen in the soil, reducing the need for purchased fertilizer.

Rotational grazing can also be tailored for multiple species. Cattle may graze a paddock first, followed by sheep that consume weeds and leftover forage. Goats can be added to target brush and woody plants. This layered approach improves pasture utilization, reduces weed pressure, and can boost average daily gains.

General land-use guidelines suggest:

- ½ to 2 acres per head of cattle

- 1 acre per 10 ewes and 15 lambs

- 1 acre per 10–25 goats

- 1 acre per horse

These are starting points; actual requirements vary with forage productivity, rainfall, and management intensity. Determining the right cow-calf stocking rates for your operation depends on balancing available forage with herd needs, as well as adjusting for seasonal changes.

Another challenge is seasonal variation. During times of slower growth—such as drought, heat stress, or winter dormancy—paddocks may require longer rest. Planning ahead with contingency sections, back-fencing, or supplemental feeding keeps both the herd and pastures in balance. Ranchers also factor in labor demands, recordkeeping, and flexibility in their schedules. Rotational grazing is more hands-on than continuous systems, but management can be adapted to fit the operation’s size and resources.

Turning Grazing Data into Better Decisions

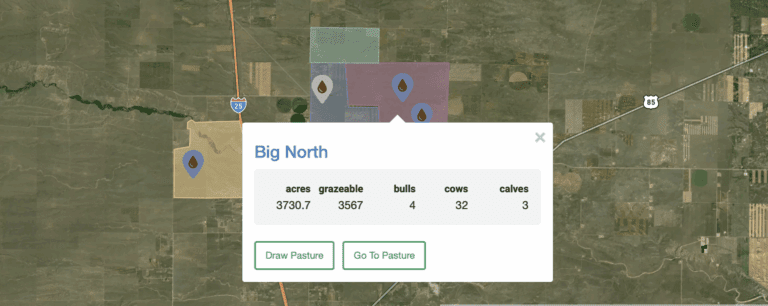

Rotational grazing requires careful monitoring and data tracking, which can be a challenge without the right system in place. Many ranchers use digital tools like CattleMax to make this process more manageable.

With CattleMax, ranchers can:

- Map pastures and mark features like water tanks, ponds, and fences

- Schedule and record animal moves between pastures

- Track pasture maintenance such as fertilization, brush clearing, and aeration

- Build a history of pasture use and conditions to see how management decisions impact long-term performance

Because records are accessible on smartphones and computers, ranchers can make informed decisions in the field and build a history of how pastures respond year after year. This not only saves time but also helps identify trends that improve profitability and sustainability.

The Payoff: Healthier Herds, Healthier Land

Rotational grazing requires more upfront planning and management than continuous systems, but the rewards quickly outweigh the effort. Improved soils, healthier pastures, reduced feed and fertilizer costs, and stronger animal performance all contribute to long-term profitability. The system also makes operations more resilient to drought, parasites, and market challenges.

By combining thoughtful planning with recordkeeping tools like CattleMax, ranchers can unlock the full potential of their land and herds. What starts as an investment in fencing and water infrastructure grows into a long-term strategy for healthier cattle, more productive pastures, and a stronger bottom line.

Jacqueline

Jacqueline, a true Wyoming native, was raised on her family's ranch just north of Cheyenne. Her journey led her to the University of Wyoming, where she earned a Bachelor of Business Administration in Management and Marketing. She and her husband, Darrell, manage a thriving herd of commercial Angus cattle.